Environmental Psychology an Introduction

Note of Environmental Psychology an Introduction

[!info] Bibliography Steg, L., & Groot, J. I. M. de. (2019). Environmental Psychology: An Introduction 2nd Edition. Wiley-Blackwell.

Environmental Psychology: History, Scope, and Methods

We define environmental psychology as the discipline that studies the interplay between individuals and the built and natural environment.

[!info] Environmental Psychology

A subfield of psychology that studies the interplay between individuals and the built and natural environment.

HISTORY OF THE FIELD

Brunswik (1903–1955) and Lewin (1890–1947) are generally regarded as the ‘founding fathers’ of environmental psychology (Gifford 2007)

Towards ‘Architectural’ Psychology

In this early period of the field of environmental psychology, much attention was given to the built physical environment (i.e. architecture, technology, and engineering) and how it affected human behaviour and well‐being (Bonnes and Bonaiuto 2002).

Environmental psychology as a study to design buildings that would facilitate behavioural functions was officially born. 早期的环境心理学集中于建筑如何影响个人的行为与健康

Towards a Green Psychology

This resulted in studies on sustainability issues, that is, studies on explaining and changing environmental behaviour to create a healthy and sustainable environment.

[!info] Sustainability Using, developing, and protecting resources at a rate and in a manner that enables people to meet their current needs and also ensures that future generations can meet their own needs; achieving an optimal balance between environmental, social, and economic qualities.

The first studies in this area focused on air pollution (De Groot 1967; Lindvall 1970), urban noise (Griffiths and Langdon 1968), and the appraisal of environmental quality (Appleyard and Craik 1974; Craik and Mckechnie 1974). From the 1970s onwards the topics further widened to include issues of energy supply and demand (Zube et al. 1975) and risk perceptions and risk assessment associated with (energy) technologies (Fischhoff et al. 1978).

In the 1980s the first studies were conducted that focused on efforts promoting conservation behaviour, such as relationships between consumer attitudes and behaviour. 1980年,第一项研究亲环境行为的研究出现。 象征着环境心理学从建筑心理学转向了绿色心理学

CURRENT SCOPE AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE FIELD

A continuing and growing concern of environmental psychology is to find ways to change people’s behaviour to reverse environmental problems, while at the same time preserving human well‐being and quality‐of‐life.

Interactive Approach

The negative as well as positive influences of environmental conditions on humans. Factors that influence human behaviour that affect environmental quality. Factors affect the outcomes and acceptability of strategies to encourage pro‐environmental behaviour for creating sustainable environments.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration

First, environmental psychology has always worked closely with the disciplines of architecture and geography to ensure a correct representation of the physical‐spatial components of human–environment relationships. Second, theoretical and methodological development in environmental psychology has been influenced strongly by social and cognitive psychology. Third, when studying and encouraging pro‐environmental behaviour, environmental psychologists have collaborated with environmental scientists, among others, to correctly assess the environmental impact of different behaviours. 由于研究目标上的特性,环境心理学注定是需要多学科合作的.

Problem‐Focused Approach

Environmental psychologists do not conduct studies merely out of scientific curiosity about some phenomenon, but also to try to contribute towards solving real‐life problems. 这正是我喜欢环境心理学的一点,它关注与解决真实生活中的问题. The problems and associated solutions that are studied vary across these levels. For example, at the local level, problems like littering and solutions like recycling may be a focus of research. At regional and national levels, problems like species loss and solutions like ecological restoration can be studied. At the global level, problems like climate change and solutions like the adoption of new technologies to combat climate change are of interest. 环境心理学从微观到宏观,都能够提供一定的研究视角.

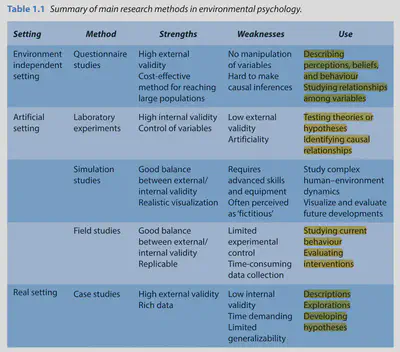

Diversity of Methods

Environmental psychology largely uses the same quantitative and qualitative methods as other psychological disciplines. Choosing a method typically involves a trade‐off between internal and external validity. Internal validity reflects the extent to which cause–effect relationships can be established. External validity reflects the extent to which the results of a study can be generalized to other populations or settings. 选择不同的方法有着不同的内外效度,不同的方法没有好坏之分,更多的集中于研究目的.

MAIN RESEARCH METHODS IN ENVIRONMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY

PART1 Environmental Influences on Human Behaviour and Well‐Being

Environmental Risk Perception

[!info] Risk The possibility that a situation, event, or activity leads to an adverse outcome.

Environmental risks differ from other risks in a number of ways. First, environmental risks are characterized by high complexity and uncertainty, entailing intricate causal relationships and multiple consequences. Consequently, they often encompass both risks for (e.g. acidification of oceans caused by anthropogenic carbon dioxide) and risks from (e.g. destruction of human habitat due to flooding) the environment. Second, environmental risks often emerge from the aggregated behaviours of many individuals (e.g. use of fossil fuels) rather than from a single activity. Therefore, mitigations cannot be easily attained, because they require actions of many people.The people who contribute to a risk (e.g. industrial countries) are not necessarily the ones who suffer the consequences (e.g. developing countries, future generations). Third, the consequences of environmental risks are often temporally delayed and geographically distant. 环境风险与常规风险存在着较大的不同,有着更大的不明确性(包括对环境的风险以及环境带来的风险)、来自大量个体减缓不易实现、存在时间延后与地理距离,导致风险制造者不会是后果承担者。因此演变成为了一种道德问题。

SUBJECTIVE RISK JUDGEMENTS

[!info] Risk perception People’s subjective judgement about the risk associated with some activity, event, or technology.

Research has developed several techniques to assess subjective risk judgements. First, respondents are asked to give an overall judgement by either rating or rank ordering various risks according to their overall riskiness or to the degree to which they experience concern, worry, or threat concerning these risks. A second approach is to ask people how much money they would be ‘willing to pay’ (WTP) to mitigate or how much they would be ‘willing to accept’ (WTA) to tolerate a particular risk. A third approach is to have respondents estimate the subjective probability of a given outcome (e.g. the probability of dying from lung cancer when exposed to asbestos). 主观风险评估的三种形式:对风险进行评估排序、接受危机或支付减少危机的意图、对结果可能性的主观评估

Heuristics and Biases in Risk Judgements

Heuristics ,that is, simple, intuitive rules‐of‐thumb, can lead to biased risk assessments. 易得性启发式与锚定调整启发式

[!info] Availability heuristic People are more likely to overestimate the occurrence of an event the easier it is for them to bring to mind examples of similar events.

People believed more in, and had greater concern about, global warming on days that they perceived to be warmer than usual (Li et al. 2011)

[!info] Anchoring‐and‐adjustment heuristic When making estimates, people often start out from a reference point that is salient in the situation (the anchor) and then adjust this first estimate to arrive at a final judgement.

People who were exposed to a high (10 °F) compared to a low (1 °F) initial anchor not only gave higher estimates for the increase in the Earth’s temperature but were also more likely to believe in global warming and were WTP(willing to pay) more to reduce global warming (Joireman et al. 2010).

[!info] Unrealistic optimism People’s tendency to believe that they are more likely to experience positive events and less likely to experience negative events than others

People tend to perceive risks of climate change, mobile phones, radioactive waste, and genetically modified food to be smaller for themselves than others (Costa‐Font et al. 2009). 非理性乐观主义的例子

[!info] Framing effects Different descriptions of otherwise identical problems can alter people’s decisions

People perceived environmental problems (e.g. river quality, air quality) as more important when the opportunity of restoring a previous better state (i.e. undoing a loss), rather than improving the current state (i.e. producing a gain).

One common explanation for framing effects is that a loss is subjectively experienced as more devastating than the equivalent gain is gratifying. 框架效应的例子与解释.

[!info] Affect heuristic The tendency to base judgements of risk and benefit on one’s affective state. If individuals feel positive about an activity, they tend to judge the risk as low and the benefit as high.

Temporal Discounting of Environmental Risks

[!info] Temporal discounting Psychological phenomenon that outcomes in the far future are subjectively less significant than immediate outcomes.

People find an oil spill equally risky whether it may happen in one month, in one year, or in ten years (Böhm and Pfister 2005).

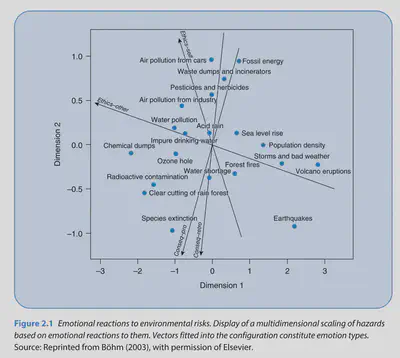

The Psychometric Paradigm

Identify the ‘cognitive map’ of diverse risk events, activities, or technologies and its underlying psychological dimensions that lead individuals to perceive something as more or less risky.

Basic dimensions of the cognitive map of perceived risk: dread risk and unknown risk.

- Dread risk describes the extent to which a risk is experienced as dreadful or as having severe, catastrophic consequences.

- Unknown risk refers to the extent to which the risk is experienced as new, unfamiliar, unobservable, or having delayed effects. 感知风险的两个维度:恐惧风险与未知风险,即问题的严重性与未知性。

RISK, VALUES, AND MORALITY

People low on traditional values (i.e. family, patriot-ism, stability) and those high on altruism (concern with welfare of other humans and other species) tend to perceive greater global environmental risks (depletion of ozone layer and global warming; Whitfield et al. 2009). 传统价值观低与利他主义高的人认为全球环境风险更大。

People who value nature in its own right (biospheric value orientation) show greater awareness while people with strong egoistic values show reduced awareness of environmental problems (Steg et al. 2005). 重视自然环境意识强,利己主义环境意识弱。

[!info] Protected or sacred values People think of such entities or values (e.g. human or animal life, unspoilt nature, human dignity) as absolute, not to be traded off for anything else, particularly not for economic values.

People holding sacred beliefs for the Indian river Ganges are less likely to perceive this river as polluted (Sachdeva 2016).

结果主义与义务主义

[!info] Deontological principles Deontological principles refer to morally mandated actions or prohibitions (e.g. duty to keep promises, duty not to harm nature), despite their consequences. The focus is on the inherent rightness or wrongness of the act per se.

[!info] Consequentialist principles Entail conclusions about what is morally right or wrong based on the magnitude and likelihood of outcomes. The aim of consequentialist principles is to maximize benefits and to minimize harms.

Protected values were strongly associated with deontological orientations, and with a stronger preference for acts than omissions. 义务主义更倾向于保护行为

EMOTIONAL REACTIONS TO ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS

Emotions influence risk perceptions. We judge risks as higher when we feel negative about an activity, but we judge risks as lower when we feel positive about it. Different specific emotions can have differential impacts. 不同的情绪会导致不同的影响。

- Fear increases and anger reduces risk perception, even though both are negative

Emotions can also occur as reactions to perceived risks When people focus on the consequences of a risk, they experience consequence‐based emotions. These can be prospective (e.g. fear arising from the anticipation of harm) or retrospective (e.g. sadness triggered by an experienced loss) 情绪既会影响风险感知也是风险感知的反应。

The emotional profiles of the risks.